As state and local governments look for ways to reduce emissions and improve the affordability and resilience of buildings, a growing number are turning to Building Performance Standards. These policies address energy waste in existing buildings and use multiple alternative compliance paths (ACPs) to provide flexibility. But not all of these alternative pathways are created equal. Some work well, some cause confusion, and some have yet to be used. It’s time to take a step back to see what we can learn to make ACPs work better going forward.

Meet the PATH Project

IMT’s BPS PATH (Building Performance Pathway Alternatives and Training Hubs) project seeks to simplify, align, and improve alternative compliance pathways. With funding from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and support from our partners–including Slipstream, the Building Energy Exchange, and 12 local and state government partners–we are creating a new model framework for ACPs. Our goal is for it to work across jurisdictions and address common challenges with BPS compliance.

What is a BPS ACP?

An alternative compliance pathway (ACP) is a common compliance mechanism in building performance standards (BPS) that provides flexibility when meeting a short-term BPS target is infeasible, while still driving energy reductions and improvements.

Our first step was to do a deep dive into what’s already out there. Our report, The Landscape of Building Performance Standards Alternative Pathways, shares a comprehensive look at how ACPs in 11 jurisdictions. We poured over countless pages of rules and standards, and asked local experts and building owners what’s working, what’s not, and how we can help. You can read the 100 page document (it’s good stuff) OR you can read on for the top 5 takeaways.

5 Takeaways on Alternative Compliance Paths

1. ACPs are essential if we want BPS to succeed

No two buildings are the same, and any number of circumstances can impact a building’s ability to meet a performance standard. ACPs can provide necessary flexibility to overcome those barriers, whether they be financial, operational, or something else.

Without ACPs, the carbon and energy saving powers of BPS might only benefit the most well-resourced buildings while leaving behind others—like affordable housing, public institutions, and historical buildings. In recognition of this, most jurisdictions with a BPS in place have chosen to include at least one ACP in their BPS. However what that ACP is and how it’s designed and implemented (and even named) varies wildly (see Appendix C in the report for details). The variation of ACPs creates a confusion for building owners and service providers. Frankly, it was confusing even for us at times. The level of variation also limits their replicability, and increases administrative burden. In order for BPS to work for all affected buildings, ACP standardization is essential.

2. Barriers abound

There are two categories of “barriers” relevant here: 1) the barriers to comply with a BPS that might lead a building owner to need to pursue an ACP, and 2) the barriers to complying with an ACP itself.

Barriers to complying with a BPS could include: the cost of efficiency measures, a lack of incentives and financing options to pay for upgrades, or a mismatch in timing between available financing and when a building needs to meet a compliance deadline. There may also be a disconnect between when upgrades are required to meet a BPS target and when those upgrades were originally scheduled in long-term capital planning cycles. Major equipment replacements like boilers or chillers are replaced on a 20-30 year timeline, but BPS compliance periods usually kick in sooner. This could mean that an owner ends up replacing equipment early at a higher cost or risks falling out of compliance with the BPS. Workforce and supply chain shortfalls can also impair compliance. How do you implement upgrades if the materials or expertise simply aren’t available? While an ACP may not necessarily fix all of these challenges, well-designed ACPs can help alleviate the problem.

Barriers related to complying with the ACP might include difficulty understanding how to write a plan or get it approved, or challenges in providing all the relevant documentation. Designing a good ACP requires providing enough flexibility to support a diversity of needs, but enough consistency to enable verifiers to fairly manage the program. Our new framework focuses specifically on minimizing administrative burden while enabling flexibility.

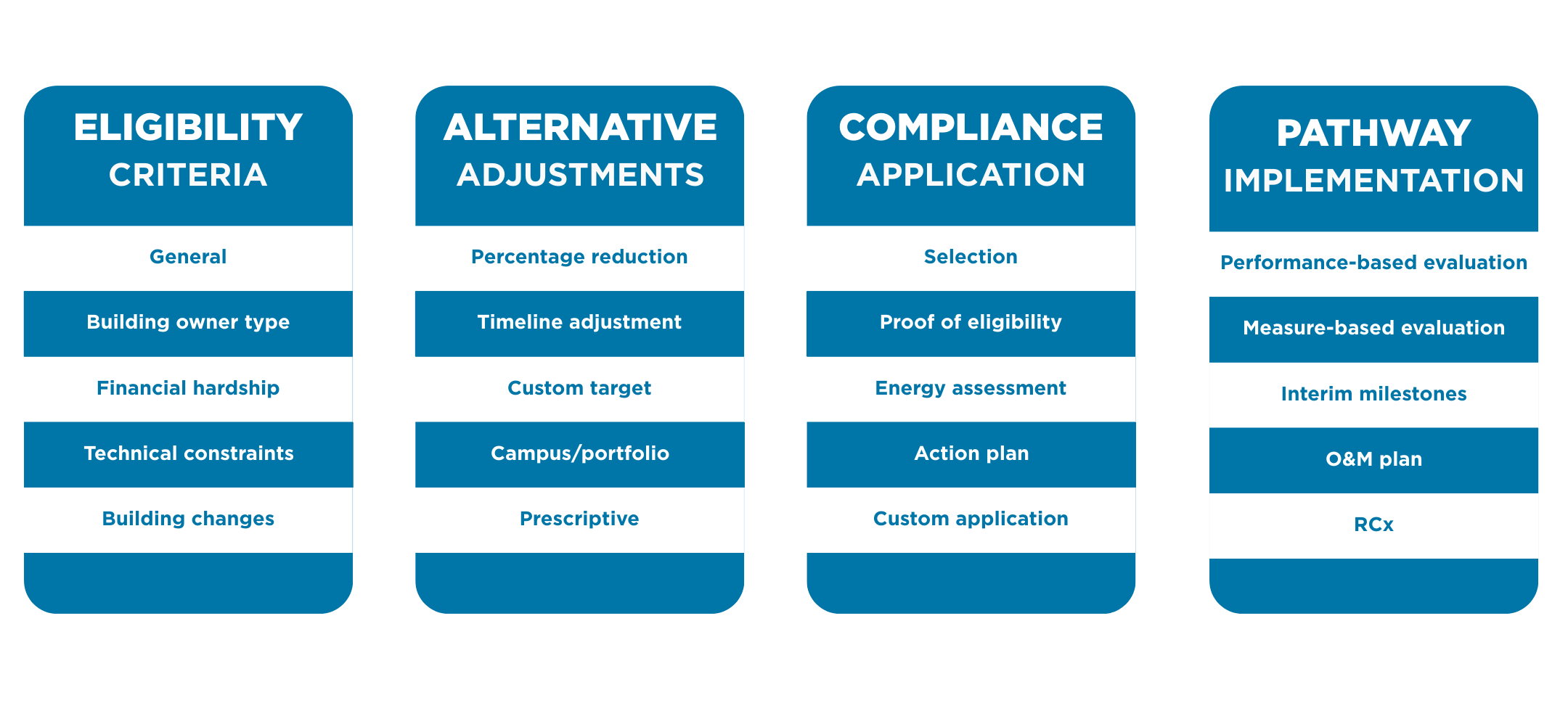

3. ACPs may look different, but all include four main elements

BPS policies are a relatively new approach to building decarbonization policies. The laws passed so far serve as tests of what is effective (or not). As a result, we’re seeing a patchwork of policies that seek to achieve common goals, but differ in many ways. For example, jurisdictions often call similar ACPs different things, or conversely, use similar names for distinctly different pathways. To do our analysis, we determined we needed a way to categorize these approaches in order to better compare them. Across all the jurisdictions studied, we noted there are at least four core ingredients to an ACP – eligibility, the alternative provided, the compliance process, and the verification process.

Eligibility: Who can use the pathway? Is it open to anyone, or only those with special circumstances or certain building types?

Alternative: The adjustment available under the pathway. The major types of adjustments that currently exist include:

- Percent reduction: a reduction in energy or emissions by a predefined percentage.

- Timeline adjustment: additional time to meet the performance standard

- Custom target: a performance target tailored for a building’s specific circumstances.

- Campus or portfolio compliance: enables multiple buildings to comply as a group.

- Prescriptive measures: a list of predefined measures to be installed, such as a high efficiency HVAC system or air sealing.

Compliance application: How a building applies and stays accountable. It may be as simple as selecting an ACP or as complicated as developing a detailed action plan.

Pathway verification: How we measure compliance. In general there are two ways this most often happens, through benchmarking and supplemental reporting or through measure-based compliance.

Note that although we have identified five categories of alternatives, we aren’t recommending that these are the five types of ACPs that every BPS should include; this is just characterizing what we’re seeing so far on the ground.

4. Impact through short and long-term policy design

ACPs are designed to offer flexibility, but they must create sufficient accountability to push real energy and emissions reductions. Jurisdictions need clear guidance, realistic expectations, and strong verification processes to ensure ACPs uphold the intent of their BPS. Flexibility is good, but flexibility without guardrails can derail the whole BPS train. On the other hand, too many guardrails (let’s call them “overly complex requirements”) can make it hard for riders to get onboard.

A percent reduction approach–where a building needs only reduce their energy use from their baseline by a predetermined percentage–has promise as a simpler short term compliance mechanism. Many buildings are very limited in what they can do in the short term to meet a fixed goal, and are better able to make operational improvements that achieve a percent reduction from their baseline. However, over the longer term, we find that these approaches will yield diminishing returns and are unlikely to be sustainable or sufficient.

ACPs need to factor in longer-term energy reduction opportunities. With good strategic planning, almost all buildings can make larger changes cost-effectively. IMT’s model BPS law contains a planning-based ACP called the Building Performance Action Plan, but has been challenging to implement. With the PATH project, IMT aims to improve this model and tie it to engineering industry best practices for easier implementation. Fortunately, there is an emerging consensus we can look to for inspiration here.

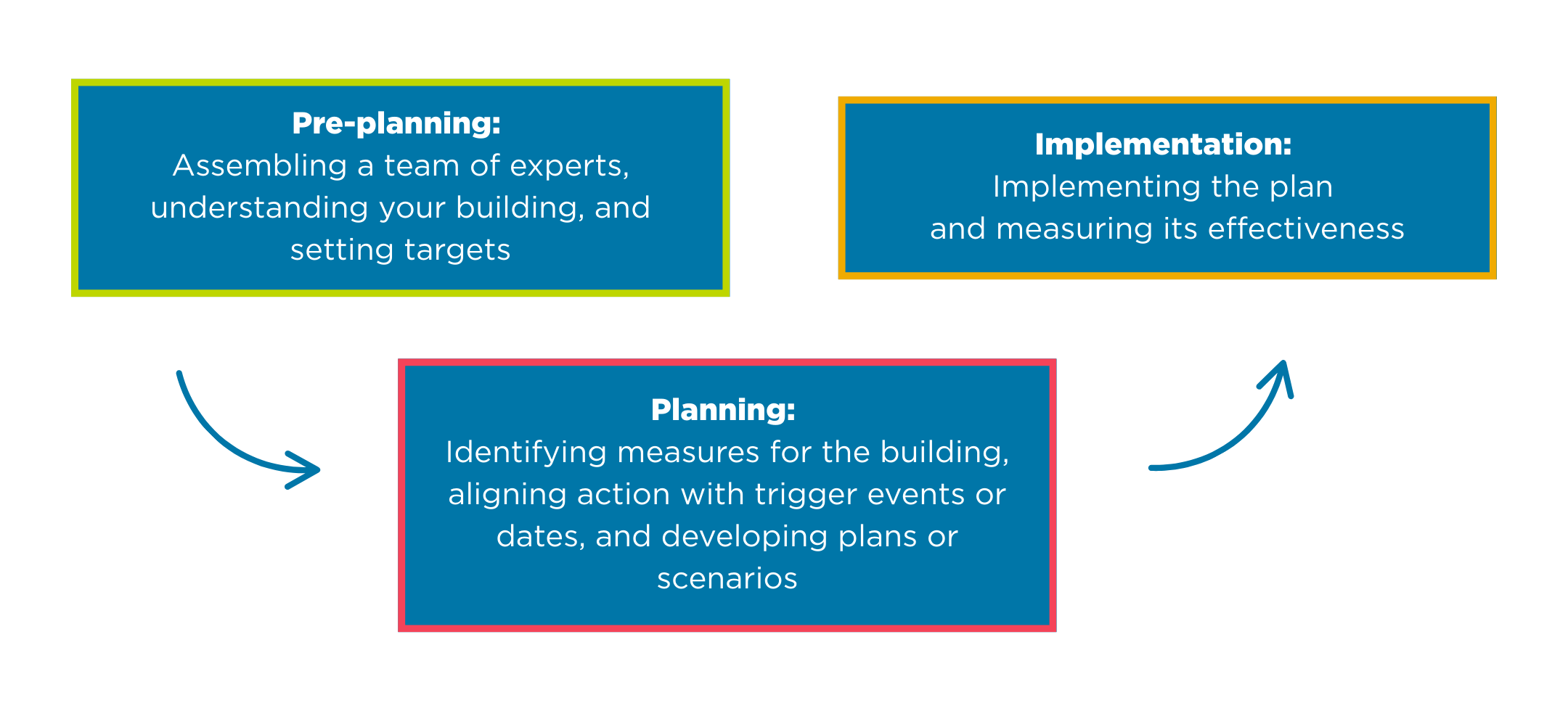

5. Strategic decarbonization planning guides

One positive sign for more standardized policies is that the industry is starting to speak the same language. Several organizations (including ASHRAE, USGBC, NYSERDA, BE-Ex, RMI, ULI, Slipstream, and DOE) have developed guidance for owners with long-term strategic building decarbonization that are well aligned, both with each other and with BPS.

Despite coming from different sources, each guide follows a similar structure with three major stages of planning:

All the guides highlight the need for energy efficiency, demand reduction measures, reduction of fossil fuel usage, and generation of renewable energy. Critically, they all recognize that major equipment will be replaced one way or another over time, and consider that replacement part of the business-as-usual scenario. Most also elevate the importance of using lifecycle cost analysis and relative net present value (NPV) in financial analysis to more fairly compare costs-and-benefits over time. The long-term approach, with clear documentation and an expectation to revisit the plan at set intervals, aligns well with any BPS with a long-term-final target. That said, it’s important to draw a line between best practices and policy requirements. Just because something in a guide is helpful doesn’t mean it should be required by a BPS or its associated ACPs. Using the frameworks as a reference, we hope to find the right balance of structure and flexibility needed to help building owners be successful. For the full list of guides and links, and our complete analysis, read our report.

What Comes Next

ACPs are a bridge between ambition and reality, enabling jurisdictions to achieve their energy and emissions goals while providing flexibility for those affected by the policies. For that bridge to hold strong, we need ACPs with solid design, clear guidance, and a shared idea of what success looks like.

We’ll be spending the next few months writing our ACP model framework with insights from our coalition of industry professionals. We kicked off a working group of experts in July and will continue to meet and develop the model framework for the rest of the year. We expect to publish the draft framework and a supporting toolkit of resources for peer review in early 2026, and to finalize the framework by mid-2026. From there, we’ll revise IMT’s model BPS law, and work with our government partners to integrate the framework into their policies as appropriate. We also plan to put the framework to the test by conducting planning pilots in real buildings to see what works and what could work better.

IMT is also co-founder of the Building Performance Partnership Network, which supports local and regional building performance improvement. Their high performance building hubs will be rolling out a series of new training materials to meet identified market needs.

To stay engaged–including to hear about our peer review–make sure you are signed up for IMT’s mailing list. We’ll also be presenting on this project at the ASHRAE Decarbonization Conference in Chicago in a session on “Making BPS Strategic on October 22.